I am certain that the Coal River Valley is precisely where I want to be. As someone madly in love with the diversity of life on Earth, it would be difficult for me to express my delight with the mixed mesophytic forests of the southern Appalachian bioregion. When the winter groundfreeze thaws, the forest floor here proliferates with spring ephemerals: bloodroot, rue anemone, dutchman’s breeches, cut-leafed toothwort, trout lillies, blue cohosh, and spring beauties. The ridgeline above the hollow I live in is like a path of the gods: wind, sun, rain, and snow can all beseige a trespasser along that path in the space of a few moments, but I would not shy from the violent beauty of that power. When climbing to the ridge, I pay homage to the great chestnut trees that once dominated the canopy here by rubbing a little bit of dirt into the open blight wound of a scraggly young chestnut that’s grappling with the fungus that killed its forebears. A native fungus in the soil inhibits the blight and helps Castanea dentata resist its assailant.

I am certain that the Coal River Valley is precisely where I want to be. As someone madly in love with the diversity of life on Earth, it would be difficult for me to express my delight with the mixed mesophytic forests of the southern Appalachian bioregion. When the winter groundfreeze thaws, the forest floor here proliferates with spring ephemerals: bloodroot, rue anemone, dutchman’s breeches, cut-leafed toothwort, trout lillies, blue cohosh, and spring beauties. The ridgeline above the hollow I live in is like a path of the gods: wind, sun, rain, and snow can all beseige a trespasser along that path in the space of a few moments, but I would not shy from the violent beauty of that power. When climbing to the ridge, I pay homage to the great chestnut trees that once dominated the canopy here by rubbing a little bit of dirt into the open blight wound of a scraggly young chestnut that’s grappling with the fungus that killed its forebears. A native fungus in the soil inhibits the blight and helps Castanea dentata resist its assailant.

On my walks, I see species I’m familiar with from the hardwood forests to the north–yellow birch, wild leeks, trailing arbutus–as well as my friends that clearly place me in a southern forest–showy magnolias and a sprawling array of wild grapes. The sheer age, the complex geology, and the north-south orientation of this mountain range have all nurtured the evolution and diversification of the ecosystem over the millennia; the mountains harbored aquatic species during dry glacial periods and allowed species to migrate at a continuous elevation with the retreat and advance of the glaciers. All of this has borne a beautiful amalgam of northern and southern taxa and the richest temperate freshwater ecosystem in the world1.

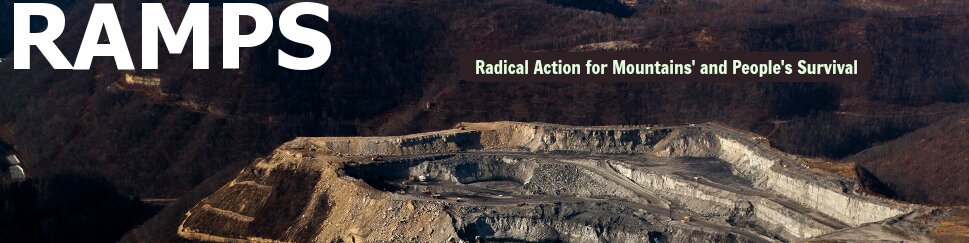

Yet the fabric of these ancient and diverse forests is being torn apart. There is no way that I can begin to detail the comprehensive destruction that surface mining and mountaintop removal wreak on the forest ecosystem of the southern Appalachian mountains. Valley fills choke ephemeral, intermittent, and other headwater streams, eliminating their function in providing organic matter downstream, increasing the sediment load, and causing flooding. Sulfuric acid released during mining leaches heavy metals that poison aquatic life and humans. The forests that are clear-cut before a mountaintop is destroyed cannot begin to grow back on a reclaimed site; the geology, hydrology, topography, substrate, and chemistry of a strip mined site cannot be manipulated to resemble those of the original forest, making reclamation an empty promise2. The soils will take a century to recover, and the mountain itself will be gone forever.

Research has demonstrated these environmental impacts and many more, but those who are drinking tainted water, breathing coal dust, and watching the mountains fall around them don’t need a scientific study to tell them what’s wrong. As I try to make senese of the world around me, I become more and more convinced that I need to understand the patterns of exploitation and oppression that permeate human society. The insidious way that the coal industry manipulates the social, political, and economic spheres in southern West Virginia toward its end of fiscal profit at all costs certainly qualifies as oppression. But beyond this, our nation’s appetite for cheap energy and the affluence it allows feed into the spiraling global crisis of industrial greed and mindless consumption. As power becomes increasingly concentrated in the multinational corporations that viciously exploit human labor in their mad rush to convert functioning ecosystems into excess material possessions for the wealthy, we lose more and more of the biodiversity that constitutes true beauty.

Surface mining, as an extractive industry, necessarily terminates in a dead end; we are running out of Appalachian coal to dig out of the ground. Only living components of an ecosystem will replenish themselves, but we usually can’t rapidly and violently extract massive amounts of these and turn them into cash. Turning to the living system to sustainably meet our needs, then, requires a very different strategy; we will have to know the land intimately. But that’s what excites me. When I’ve spoken with elders in rural communities who know a myriad of edible and medicinal herbs and how to find and prepare them all, I wonder why more young people don’t have this knowledge. Instead of allowing Appalachia to be a sacrifice zone for our short-sighted permissiveness of corporate control of our lives, we can learn from Appalachian traditions of self-sufficiency, wildcrafting, rootedness in place, and community solidarity.

I feel, with the keen urgency of extinction, that Alpha Natural Resources cannot be allowed to tear apart Coal River Mountain and allow all those living below it to suffer for their profits. Legal resistance to strip mining has been failing for decades; we can’t allow ourselves to be gulled into believing that we should confine ourselves mildly to sanctioned channels for change while those who profit from exploitation set the terms. We need to throw everything we can into the gears of big coal, costing them as much money and shame as possible. To this end, I am going to sit about fifty feet up in a tree for as long as I can.

I’m sitting for those who are depressed because they are manipulated and imprisoned by a system that breeds a festering discontent in order to sell products of global pillage. I’m sitting for the salamanders and tardigrades that are being buried in rubble. I’m sitting for my little sister who has asthma from breathing coal-polluted air. I’m sitting for Junior Walk, whose stomach has been poisoned from a childhood of drinking mine-polluted water. I’m sitting for all those who don’t have safe well water because the land around them was ravaged to support the coal-based electricity that I have been using all my life. I’m sitting because I can confront the coal industry publicly without losing my job or the support of my family or community.

In other words, I do this out of passion, and I do it out of love. I do it as an act of anger and of penance. I do it out of obligation and out of freedom.

If you haven’t begun already, I invite you to join us in the fight.

- Ricketts, T.H., E. Dinerstein, D.M. Olson, C.J. Loucks, et al. 1999. Terrestrial Ecoregions of North America: A Conservation Assessment. World Wildlife Fund – United States and Canada. Island Press, Washington, D.C. pp. 337-340.

- M.A. Palmer, E.S. Bernhardt, W.H. Schlesinger, K.N. Eshleman, E. Foufoula-Georgiou, M.S. Hendryx, A.D. Lemly, G.E. Likens, O.L. Loucks, M.E. Power, P.S. White, P.R. Wilcock. 2010. Mountaintop Mining Consequences. Science 327(5962):148-149.